"Cosmic Banking" from Omnibus

To keep my bare knees from meeting the Coca-Cola red shag carpet, I set a couple throw pillows on the floor—makeshift zafus from Home Goods, Delafield. Susan will never know, as long as I remember to replace them on the Coca-Cola red leather couches. I face the TV, which is off, because otherwise my view is of the staircase, and the whole idea here is to leave this plane behind and forget everything, especially what lays behind the door at the top of the basement stairs—meaning, the wider world, but also the particular world that contains Wales, Wisconsin, and Washington D.C.

I do my usual warm-up and stretch, a pose that my wife used to teach as “Ego Eradicator,” a term coined by a self-styled Californian yogi from the ‘70s who called himself Yogi Bhajan (pronounced by his most deludedly sacrosanct devotees as “budgeon”). Until recently, Budgeon, as I will call him, was known for “bringing Kundalini yoga to the west.” That his reputation lasted as long as it did for this repudiated feat is evidence of the masterful way that this man, born in India in the 1930s, controlled his narrative. For it was disclosed publicly on a podcast in 2020, which my wife and I listened to on our drive to the Midwest, that Budgeon had told a great many lies about the origins of Kundalini. The most fantastic one is about how he went to a mountain cave where the “kriyas” (set sequences of poses, postures, movements, breaths, chants) had been guarded for 10,000 years, and then like a cross between Moses and Tarzan, absconded with them, swinging out of the cave on a rope attached to a helicopter.

To be alive in 2020 is to know tremendous fear and uncertainty, but also to witness the long-overdue toppling of some corrupt institutions. Budgeon’s luck ran out, and some confluence of #metoo waves, the pandemic and the end of the Trump presidency brought about the long-overdue unveiling of the truth around him, a man whose colleague some in the ‘80s called “The Toner Bandit” for his money-making scheme involving the resale of computer ink. In 2020, a tell-all memoir hit the market, written by a woman who was sexually, physically, and mentally abused by Budgeon expressly in his role as religious leader. To call it an unravelling is apt, because an easy likeness was drawn to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh character who was worshipped by all those Oregonians—a tale told to acclaim in the Netflix series Wild Wild Country. In the course of a year Budgeon went from having a cult following to being reviled as much as Bikram, Kevin Spacey, and Bill Cosby.

~

I STARTED DOING YOGA in 2014 with Theresa, then my live-in girlfriend, after she went through Kundalini teacher training (an abusive experience by all accounts) and opened a studio in the upstate town nearest our home. In this funky little town, she bought a building, opened a second-floor studio, and there we did yoga together every week along with some members of the community. Four or five years this went on, until Theresa tired of Kundalini’s didacticism and stridency. Then she dropped the tune-ins, and began modifying kriyas to her liking and dropping the closing “hymn,” “The Long-Time Sunshine Song,” which Budgeon required all kriyas to be concluded with.

For another year or two she taught yoga in a manner to her liking and continued to play gong. Then the tell-all memoir hit, and the pandemic awoke her to the true extent that running this studio depleted her energies, and she basically stopped practicing yoga. Me, I kept up the practice on my own, doing some of the poses and breath exercises. But today I no longer chant the Sanskrit or Gurmukhi chants either. She used to make huge pots of tea with cardamom, cloves, and ginger. It was known as Yogi Tea. Today we call it Yummy Tea instead. We even changed the core poses like Ego Eradicator. Instead of the hand mudra of bent knuckles and inwardly pointing thumbs that Budgeon said made certain energy flow in certain ways—I use blade-like hands, fingers straight. I no longer focus on pumping the navel like a bellows to create fire but think of our fingers as prongs plugging into sockets in the sky, from which we receive the energy of our “highest self.” All the little pseudo-scientific mumbo jumbo that Budgeon fabricated in a vain and incoherent program of mega-cultic control—these I replaced with whatever I fancied. This is the offering of the pandemic: a transition from long-held, unquestioned falsehoods. Unfortunately, so many of us are apparently afraid of a reality free from falsehoods—and in response take part in growing the numbers.

Now, I own it. Now I control the narrative of what we’re doing. I’m longer doing “Kundalini Yoga as Taught by Yogi Bhajan.” I’m not even necessarily doing Kundalini yoga.

~

THE CARPET swings in and out of view as I breathe in, lifting the head up, and exhale, looking forward.

Three minutes. The entire time, my mind is occupied with whether Gerald or Susan will come through the door at the top of the stairs, start descending, then react in some aghast, confused way when they see their son-in-law in a strange posture on the floor, chest heaving. But I focus on my rapid in and out, seeing the black backs of my eyelids. Seeing the colorful blob at my third eye.

After my warm-up poses and a couple cracks of the neck and back, I do my usual set that targets the fifth chakra. I know the word chakra really riles some people into flaming condescension. There are some who in response to “new age” jargon don a veritable straight jacket of rationality, complete with Christian shoulder pads and tied by a snazzy Carl Sagan belt. And that’s fine, I can’t help that. But all I want you to be aware of is that I never thought I’d be living in the woods doing yoga and drinking turmeric tea either, but since 2014 I’ve found this practice really helps my mental health, and even helps my writing.

My worst fear is realized when I hear the sound of the upstairs door and the heavy clomp of Susan’s feet. “Oh, sorry, Ben. I didn’t know you were exercising.”

“No problem!” I say cheerfully.

She goes to the basement fridge for (apparently) some apples.

~

NOW, we are getting closer to our subject, Ram Dass.

The Gurmukhi chants that Budgeon ripped off from the Sikhs were all new to me when I learned Kundalini yoga in 2014. As a language guy, a writer, I was challenged. What does it mean, this oft-used phrase Sat Nam? Students would walk in the door calling out “Sat Nam” like a greeting. Technically, it was supposed to translate to something like “truth is my name.” Budgeon’s kriyas called for “mentally vibrating” sat nam with every inhale and exhale. Then there was wahe guru (wah-hay goo-doo), which the real devotees, who wear white and turbans, slung around like it was a part “aloha” and part “Open Sesame” of the mind.

I didn’t believe the sounds were capable, as Budgeon professed, of unlocking potential, or bring prosperity, or any of the other pseudo-medical claims. But singing these phrases offered several pleasures. The words were free of connotation and association. Ajay alay, aboo ajoo, anass akass, and so on. To chant long strings of random syllables, completely blank in their meaning for 11 minutes creates an experience like the character has in Chris Cornell’s lyric to the song “Doesn’t Remind Me”;

I like speaking in tongue

and breaking guitars

because it doesn’t remind me

of anything

Chanting like this in a room with others, remembering the sequences, maintaining concentration, not succumbing to self-consciousness—not saying, hold on, this is stupid!—requires powerful poise. It directs the mind and calms the spirit. Interestingly, rather than yoga’s “fru-fru” qualities, what endeared me to yoga was the scientific data: I experienced more peace and calm, and lower anxiety, greater relaxation and openness after doing it. The evidence was indisputable.

In Kundalini circles, there were a great many mystical artists making tunes using the Gurmukhi phrases found in Budgeon’s kriyas, pairing them with simple, repeating melodies. My wife often spun a huge playlist of these during classes that she led. One of the other songs or chants that came and went through my ears was the phrase “Guru Ram Dass.”

I didn’t know what was meant by this. I knew Ram was a Hindu deity, but that also there was a self-help type guy who put out books and tapes in America, and actually spoke at the Omega Center, near where I lived. He went by the name Ram Dass. But I’d never read him or heard him speak or really knew what topics he spoke on exactly.

I asked for clarification remarkably late—as long as three or four years from the time of my introduction to Kundalini and the likely time that I first heard some peaceful people singing “Guru Ram Dass.” What prompted me to find out about him was his death. In December 2019 when I heard that Ram Dass, the American author, lecturer, workshop leader, had passed away, I asked my wife if this was the person that the mantra music tune referred to.

In other words, this was my first introduction to Ram Dass—which somehow, unpredictably, in the trauma-stirred climate of 2022, became a point of contention between myself and Keith. Theresa explained that Ram Dass meant follower of Ram, and that he had been a Harvard professor of psychology, later went to India, and published the book “Be Here Now.” The song, she said, was invoking an ancient deity or devotional figure.

At some unspecified time that could be verified by my phone’s Stitcher App history, I began listening to Ram Dass’ “Be Here Now” podcast. I began with Episode 1, which had aired originally some 6 or 7 years prior (but whose contents were from the ‘60s). One by one, starting in January 2020, I listened to the other episodes, in the order they were made. Most often I listened while driving. The stories, his speaking manner, and ultimately his recommendation of detaching from one’s identity, from the conceptual model one has of oneself, intrigued me acutely.

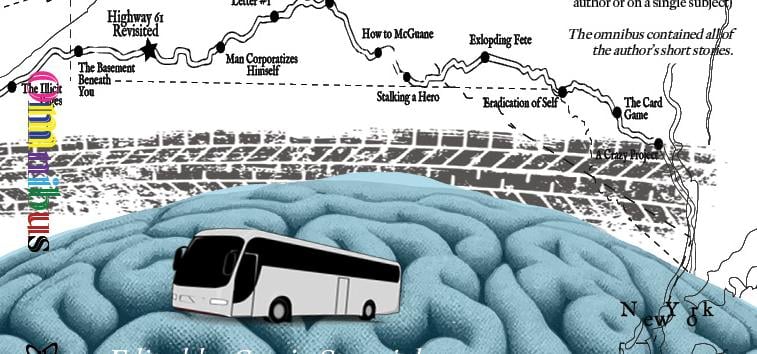

In my thirties I had begun doing Zen meditation and reading Pema Chodron; I’d also been through a 12-step program, which required some serious spiritual restructuring. So Ram Dass’s messages weren’t entirely out of left field. But they hit me hard, harder perhaps than I’d expected. The pandemic surely must have had everything to do with it. (Feel the bus lurch as the driver wrenches it firmly into his lane of choice.)

We all understand there was an edginess to the pandemic years, when no one could say how many humans would be dying across the planet, or if the earth would ever heal. RD’s speaking manner, his benevolence, humor, and insight, leavened this. At the start of 2020, capitalism’s failures become more and more starkly apparent. Income equality, environmental destruction, nations vying for resources, coastlines eroding…an upper-middle-class professional felt more and more pressured to take advantage of the economic system that could, if gamed, earn one a protections from life-threatening shortages, and the other privileges of survival. But this hardly seemed like a solution to anything—least of all the problems of our civilization.

By the time I listened to Episode 30 of “Be Here Now,” then 40, then 70, I’d absorbed the message pretty well and tried to incorporate his wisdom in ways that could relieve my own suffering. What I found is that it often worked. Just fuck it. Who cares? Stressed about whether your writing is accepted or rejected, makes you a penny, or earns you the status or success? Answer: Don’t strive to have that identify. Stop wanting to be that writer. Stop identifying as a writer at all. Why not? Nobody says you have to. It’s just a mental model you’ve adopted into your personality.

On the one hand it’s ultra-basic, and I had read Buddhist philosophy a decade prior. But now, this was different. This wasn’t a technique that you did for 20 minutes on a mat. This was a life attitude, a belief, a tenet, to adopt. What if I did it around my writing, around my Aspiring Writing Syndrome? What if the cure to the syndrome was to not identify as sick?

Tellingly, this takes me to a line from my favorite novel, Thomas McGuane’s The Bushwhacked Piano: “You are in the habit of illness.” It’s spoken by a doctor to a hypochondriac entrepreneur who is helping the novel’s protagonist win his love, the rich General Motors heiress daughter Ann Fitzgerald, by building bat towers that will eradicate the “pus-filled syringes” that are mosquitoes. But that’s neither here nor there. Or is it?

By the second term in Zoom, Summer 2020, I found myself working with three groups of 14 writers. To attend to the ambitions of 42 writers required putting aside my own ambitions. I taught with as much compassion and care as I could. I put a lot into it. I gave and gave and told myself that my own shit didn’t matter. And I came to believe it, even as I used scenes from my own work occasionally in lessons on setting and pace. I was rewarded with students learning, writers writing better and describing to me there pleasure in trying new techniques, discovering new material, and having fun writing. And then interestingly, when I did attend to my own creative work, there was more “there” there, to put terribly. I felt emboldened to blow up some of the conventions that I taught and also to embody the strongest aspects of all the craft topics I taught, and most of all, to entertain with the audacity of my choices. My prose, under the influence of Ram Dass, seemed to allow for new possibilities.

To think…letting go of my identity as a writer. The books on my shelf aren’t me. The things I’d written aren’t me. Stop believing that my life would begin in a more real, more valuable, more true way, if and when my particular preference for my professional outcomes were to be realized. I never expected to be a so-called “household name,” that’s for sure, but I have wish to be a recognized name in every fifth New York apartment building, perhaps. Ram Dass had said many times, quoting a Taoist holy text: “The great way is easy for those who have no preferences.” My preference was that I be a writer of at least some repute. Now I was shredding that preference as best I could.

Not just keeping it secret, but really shredding it.

“Beholden” is another word Ram Dass used frequently, and I began to try out the perspective that me being a writer was just an idea I’d become beholden to at some point in my past. An idea that once adopted, I clung to evermore consummately. As global-scale anxiety descended on me, I changed from thinking that writing would save me, to believing that I could save myself from writing.

Recently I learned that the Bhagavad Gita advises that a person attends to their work in Krishna consciousness but does not “revel in the fruits of his labor.” I think I started to do that. Ram Dass’ attitudes allowed some of my constructs to dissolve. I found myself more clear-eyed when writing feedback to students.

To a student in Saturday morning’s Creative Writing 101, who had written about the betrayal and forgiveness of a friend, I wrote in the teacher/student portal where homework was submitted and my feedback posted:

“Writing can be used in many different ways. We can say something about the world, the things we see going on outside of us, in society. But we can also look within and find the words for what our experience is like. That’s not always easy. We might want to do it, but lack the experience. We might want to do it, but find it scary.

“In time, I think it’s possible for our writing to be a comfort to us. We can write to ourselves just for the sake of it, to keep ourselves company, to process our experiences in relationships, in work, in life. It doesn’t have to be shared. And as we grow more comfortable with that process, you can do like you’re doing here and capture thoughts and feelings about someone else. We don’t have to write to another person, but by writing about what’s going on with them, we can identify how we feel and that can help a lot in how we deal with them. In fact, it has the power to change the relationship entirely. Just by spending time writing. That’s pretty amazing!”

How priceless that all sounds. But was it true? Was it really a solution to our deepest crises? Would it break our most stubborn dharmic patterns or behaviors? It wasn’t going to keep us under the 1.5 degree C threshold, set at the 2015 Paris climate talks, that was for sure.

~

MY INTRODUCTION to Ram Dass’ body of work led me to write a piece that I worked on in my in-laws’ Wales, Wisconsin, basement between work tasks, and in the yard of the Fox Lake cabin, and even poolside, in my head, as I applauded Maxine’s talent at diving for rings. It came together the second summer, 2021, and gave me a chance to air a piece of spiritual dirty laundry about a missteps I took with writing students, one which is captured here, and the other, with Keith, which would be far worse and was still to come.

Cosmic Banking

Can we transact between creative and financial accounts?

Over seven years ago, I heard something uncommon: a novelist interviewed on a Wall Street report radio program. The novelist was Mona Simpson. Forgetting the supernatural suavity of host Kai Ryssdal’s voice, let us look at these wise words from his “Marketplace” guest of June 6, 2014. This is my transcript of the end segment titled (with classic Ryssdalian aplomb) “Here’s the Thing.”

For best results, please put your feet up when reading.

Ryssdal:

Here’s the thing about numbers—economic numbers, anyway: You gotta put ‘em in context. In context in the economy, of course, but also in our culture, or all you’ve got is statistics. So to wrap up our author’s series today—people who are in the business of words—author Mona Simpson.

Simpson:

[…] When I was in my twenties and trying to write my first novel, I thought it would change my life. I believed if I could sell my first novel, my life would completely, completely change. And I spent five years supporting myself—you now, sort of hand-to-mouth with part-time jobs as my student loans were coming due and my socks were wearing out. You know, when I went to a party, I wore the same dress, for years, that my mom had bought me on a visit.

[“My socks were wearing out.” I love that. — Ed.]

Simpson:

And then when I did sell the novel, the first offer the publishing company made for it was $10,000. And my agent said, “Well, she has a lot of student loans.” So it got up to $12,500. And if you look at those numbers, you think, “Well, amortize that [over] five years—it’s not very much money.”

And yet publishing my first novel did change my life in many more ways than money. [People ask me], “Do you make a lot of money?” And the answer is, you know—“No.” Novels take me four or five years, sometimes ten at the most, sometimes three at the least. And if you amortize the money fiction writers earn from them—we’re not CEOs. We’re not hugely successful in that way.

But, on the other hand ... you’re spending most of your life making something that you find beautiful and that’s deeply satisfying and fulfilling. And, you know, in a way, love is the real economy. If you’re spending your time—which is really the scarcest commodity there is—if you’re spending that doing something that gives you a lot back, that’s a kind of love.”

Well, that took a surprising turn. A finance show brings us a message about the economics of love.

Now let’s add to this something I heard much more recently. It’s February 2021, and I’m in my car playing the Ram Dass “Here and Now” podcast.

If you know Ram Dass and his many lectures, you won’t be surprised to hear that in this talk he’d been waxing eloquent about the usual things, such as how everything is energy and how his Indian guru, Neem Karoli Baba, was often locked into rooms overnight only to be found walking down the road at dawn.

[43 mins]

“What is your time worth? What are you about?

Well, my time is worth $20 an hour.

How poignant. How poignant.

How much an island unto yourself.

How little energy if your life is only worth $20 an hour.

My life is worth everything. And nothing.

Both.

My time is valueless. It’s invaluable.

I just can’t estimate what my life is worth.

…

‘Had ye but faith, you could move mountains,’ said Jesus.

Well,… Boy, it costs a lot to move a mountain! (Dass, 2014)

In other words, he’s doing what Simpson did: finding some equivalence between the spiritual and economic. Is it a false equivalence? Though he’s musing for moments in the voice of someone reality-based, he’s only doing this to contrast it with the fantastical-sounding perspective of a spiritual economist, who makes a strong valuation of life. Butting up against Christ’s teachings, the real-world grounded perspective sure sounds naïve. Which is precisely Ram Dass’s point.

The leap from one context to the other makes the position absurd. Our lives are not a quantifiable asset, a currency, like you’d find circulating in a market, or in an economy. Our lives transcend that.

Let’s point out that some would call this a “religious” view. I’m not concerned with that term.

I’m concerned with the fact that there’s no bank that can tell us the balance in our life account. A writers’ work is nothing like that of the laborer or the careerist, the professional, the office drone. (Nor, for that matter, is it as important as that of the surgeon, teacher, and many others.) Yet, we live in a world where an accountant would be quick to tell you that the price of mountain-moving services isn’t worth a damn on paper; but if someone is willing to pay for said services, then it’s has meaning. Until then, it’s theoretical.

So…

So you’re spending your time doing your writing, doing your art, working on your stories, your prose. It’s what you’re spending your life on. That’s a big deal. And it’s true for writers of all kinds: the hopelessly devoted, the dabblers, the weekend warriors. But the point can’t be the quantity or quality or your output. You’re investing your life.

Follow this calculus. (I’ll see if I can.)

If we’re all of inestimable value, and no one requires you to write (the world has no official use for your writing), you must THEN be doing it because you love it. So do it with that love. Don’t do it out of bitterness or spite or for ego. The value of your life is too high to spend it on any lesser good (double meaning intended).

Like Mona Simpsons says, the economics of writing are that the returns are great. They just aren’t monetary. So realize that and don’t operate in delusion. Also, like other transactions, you do have to invest it to get the return. You can’t want to be the next _________ and hope you’ll just luck into it like the lottery. You have to put into it what your life is worth. Put what your life is worth into what you express on the page. That means not selling yourself short, and not selling your reader short.

How do you do that?

Wait a second. Selling the world short. You mean like a short sale? Like those crummy shrub fund — I mean hedge fund managers do, the ones that Redditors just showed a thing or two to?